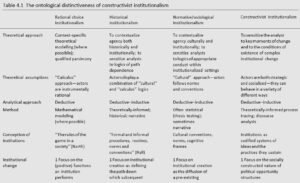

Constructivist institutionalism, as I will label it, has its origins in attempts to grapple with questions of complex institutional change—initially from within the conWnes of existing neoinstitutionalist scholarship (see also Schmidt 2006).2 In this respect, rational choice and normative/sociological institutionalism proved most obviously limiting (see Table 4.1). The reason was simple. Constructivist institutionalists were motivated by the desire to capture, describe, and interrogate

institutional disequilibrium.3 As such, rational choice and normative/sociological institutionalism, which rely albeit for rather diVerent reasons on the assumption of equilibrium, were theoretical non-starters.4 Unremarkably, then, and by a process of elimination, most routes to constructivist institutionalism can trace their origins to historical institutionalism (see, for instance, Berman 1998; Blyth 2002; Campbell 2001, 2004; Hay 2001, 2002; McNamara 1998; Schmidt 2002).

Yet if historical institutionalism has typically served as an initial source of inspiration for constructivist institutionalists, it has increasingly become a source of frustration and a point of departure. For, whilst ostensibly concerned with ‘‘process tracing’’ and hence with questions of institutional change over time, historical institutionalism has tended to be characterized by an emphasis upon institutional genesis at the expense of an adequate account of post-formative institutional change.5 Moreover, in so far as post-formative institutional dynamics have been considered (for instance Hall 1993; Hall and Soskice 2001; Pierson 1994), they tend either to be seen as a consequence of path dependent lock-in eVects or, where more ruptural in nature, as the product of exogenous shocks such as wars or revolutions (Hay and Wincott 1998). Historical institutionalism, it seems, is incap- able of oVering its own (i.e. endogenous) account of the determinants of the ‘‘punctuated equilibria’’ (Krasner 1984) to which it invariably points. This, at least, is the charge of many constructivist institutionalists (see, for instance, Blyth 2002, 19–23; Hay 2001, 194–5).

If one follows Peter A. Hall and Rosemary C. R. Taylor (1996) in seeing historical institutionalism as animated by actors displaying a combination of ‘‘calculus’’ and ‘‘cultural’’ logics, then it is perhaps not diYcult to see why. For, as already noted, instrumental logics of calculation (calculus logics) presume equilibrium (at least as an initial condition)6 and norm-driven logics of appropriateness (cultural logics) are themselves equilibrating. Accounts which see actors as driven either by utility maximization in an institutionalized game scenario (rational choice insti- tutionalism) or by institutionalized norms and cultural conventions (normative/ sociological institutionalism) or, indeed, both (historical institutionalism), are unlikely to oVer much analytical purchase on questions of complex post-formative institutional change. They are far better placed to account for the path-dependent institutional change they tend to assume than they are to explain the periodic, if infrequent, bouts of path-shaping institutional change they concede.7 In this respect, historical institutionalism is no diVerent than its rational choice and normative/sociological counterparts. Indeed, despite its ostensible analytical con- cerns, historical institutionalism merely compounds and reinforces the incapacity of rational choice and normative/sociological institutionalism to deal with dis- equilibrium dynamics. Given that one of its core contributions is seen to be its identiWcation of such dynamics, this is a signiWcant failing.

This is all very well, and provides a powerful justiWcation for a more construct- ivist path from historical institutionalism. It does, however, rest on the assumed accuracy of Hall and Taylor’s depiction of historical institutionalism—essentially as an amalgamation of rational choice and normative/sociological institutionalist conceptions of the subject. This is by no means uncontested. It has, for instance, been suggested that historical institutionalism is in fact rather more distinctive ontologically than this implies (compare Hay and Wincott 1998 with Hall and Taylor 1998). For if one returns to the introduction to the volume which launched the term itself, and to other seminal and self-consciously deWning statements of historical institutionalism, one Wnds not a vacillation between rationalized and socialized treatments of the human subject, but something altogether diVerent.

Thelen and Steinmo, for instance, are quite explicit in distancing historical institutionalism from the view of the rational actor on which the calculus approach

is premised. Actors cannot simply be assumed to have a Wxed (and immutable) preference set, to be blessed with extensive (often perfect) information and fore- sight, or to be self-interested and self-serving utility maximizers. Rational choice and historical institutionalism are, as Thelen and Steinmo note, ‘‘premised on diVerent assumptions that in fact reXect quite diVerent approaches to the study of politics’’ (1992, 7).

Yet, if this would seem to imply a greater aYnity with normative/sociological institutionalism, then further inspection reveals this not to be the case either. For, to the extent that the latter assumes conventional and norm-driven behavior thereby downplaying the signiWcance of agency, it is equally at odds with the deWning statements of historical institutionalism. As Thelen and Steinmo again suggest:

institutional analysis . . . allows us to examine the relationship between political actors as objects and as agents of history. The institutions that are at the centre of historical institutionalist analysis . . . can shape and constrain political strategies in important ways, but they are themselves also the outcome (conscious or unintended) of deliberate political strategies of political conXict and of choice. (Thelen and Steinmo 1992, 10; emphasis added)

Set in this context, the social ontology of historical institutionalism is highly distinctive, and indeed quite compatible with the constructivist institutionalism which it now more consistently seems to inform. This brings us to a most important point. Whether constructivist institutionalism is seen as a variant, further develop- ment, or rejection of historical institutionalism depends crucially on what historical institutionalism is taken to imply ontologically. If the latter is seen, as in Hall and Taylor’s inXuential account, as a Xexible combination of cultural and calculus approaches to the institutionally-embedded subject, then it is considerably at odds with constructivist institutionalism. Seen in this way, it is, moreover, incom- patible with the attempt to develop an endogenous institutionalist account of the mechanisms and determinants of complex institutional change. Yet, if it is seen, as the above passages from Thelen and Steinmo might suggest, as an approach predicated upon the dynamic interplay of structure and agent (institutional context and institutional architect) and, indeed, material and ideational factors (see Hay 2002, chs. 2, 4, and 6), then the diVerence between historical and constructivist institutionalisms is at most one of emphasis.

Whilst the possibility still exists of a common historical and constructivist institutionalist research agenda, it might seem unnecessarily divisive to refer to constructivist institutionalism as a new addition to the family of institutionalisms. Yet this can, I think, be justiWed. Indeed, sad though this may well be, the prospect of such a common research agenda is perhaps not as great as the above comments might suggest. That this is so is the product of a recent ‘‘hollowing-out’’ of historical institutionalism. Animated, it seems, by the (laudable) desire to build bridges, many of the most prominent contemporary advocates of historical

institutionalism (notably Peter Hall (with David Soskice, 2001) and Paul Pierson (2004)) seem increasingly to have resolved the calculus–cultural balance which they discern at the heart of historical institutionalism in favor of the former. The bridge which they would seem to be anxious to build, then, runs from historical institutionalism, by way of an acknowledgment of the need to incorporate micro- foundations into institutionalist analysis, to rational choice institutionalism. This is a trajectory that not only places a sizable and ever-growing wedge between cultural and calculus approaches to institutional analysis, but one which essentially also closes oV the alternative path to a more dynamic historical constructivist institutionalism.